Our Position

“I don’t have a single American friend, I don’t understand them.”

Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the older Boston Marathon bomber, to a photographer in 2009 (Olsson, 2014, p. 1)

1. Introduction

Radicalization towards all types of violence (jihadi, extreme right, anti-semitist etc.) and polarization are two major societal challenges that tear at the social fabric of Europe. Radicals incite to baleful action by framing the status quo as “unjust,” “exploitative,” “oppressive,” or “heretical.” (Hafez, 2015), while polarizers work in the opposite direction, inviting society to show no mercy to the different and the differences. Overall, the two symbiotically feed each other and catalyze confrontation.

On another far corner of the field, the proponents of the secularization theory, that have been for long arguing the religions would finally disappear from the face of earth in their battle with modernization processes, have proven to be wrong in their premise. Especially the turbulent Middle East and Europe in the last decade have clearly shown the religions do not disappear but persist, change and adapt to keep their important place among their followers.

Against this background, EDUC8 to Build Resilience Project or EDUC8, in short, was conceptualized to vehicle religious education and hence religion[6] to counter pernicious effects of radicalization and polarization. This policy brief aims to bring a fresh perspective to the nexus between religion, radicalization, and polarization, and to offer EDUC8 as an instrumental tool that can be benefited from in the fight against these two societal challenges.

2. Terror – Religion – Polarisation Nexus

The murder of a homosexual man in Beveren, Belgium on 6 March (Belga, 2021) and the Vatican’s ruling in less than ten days after the event that priests can’t bless same-sex unions (Povoledo & Graham, 2021) prompted media in Belgium to scrutinize the connection between violence and religion. The Belgian Parliament invited all representatives of religions and worldviews to the Parliament for consultation. As it becomes clear from this example, the link between religion and violence -often combined with suspicion that the former fuels intolerance and terrorism- currently is and will be a recurrent phenomenon in the future. There is an obvious need to discuss the role of religion among other factors in leading to radicalization towards violence.

Humans live within a universe of factors that on constant basis shape their look towards life and affect the meaning they attribute to it. Scholars working on radicalization often list factors like grievances, family and social connections, ideologies, socio-economic conditions as important drivers of radicalization. Religion in many cases forms the core of the respective ideology. As there is no single pattern or profile to identify who will likely radicalize and who won’t, it is equally not possible to attribute a universally valid weight to the religion among other factors. The context in which the radical grows defines the respective weights in the procedure. Research including semi-structured interviews with 63 ISIS defectors by Speckhard et al. shows how different contexts can create different motivations among target groups. The study shows for the Westerners, “offers of a real salary, arranged marriages, sex slaves for men, traditional living for women, free housing and other amenities, along with the honors bestowed by ISIS on foreign fighters who come to Syria and Iraq were real attractions as many felt their lives to be lacking dignity, purpose, significance, and honor” (Speckhard, Shajkovci, & Yayla, 2018, p. 7) The research corroborates Hafez’s position that there is need for multifactor and contextual approach that evades looking at radicalization as a uniform and linear process (2015).

Speckhard’s study does not list religion among the motivations either. Along the same lines, one deradicalization officer in Brussels told the first author in an interview: “In each case we see a person making the travel to Syria and Iraq, if we scratch the surface [if we delve deeper into the issue], we find a familial, social or economic problem. The perceived urgency or greatness of that problem pushes the person to think if he goes, he will have a better life there and leave that problem behind.” (Sultan, 2020, p. 17)

In cases where religion is openly stated, the veracity of this statement also requires further scrutiny. Redouan Safdi is a Belgian imam who is involved in the deradicalization of foreign terrorist fighters alongside homegrown terrorists and radicals in a Belgian prison. He says:

“When dealing with such a person, trying to start a deradicalization program, the first question I would always ask is, ‘Why did this person go [to a conflict zone]?’” During his inquiries into the real causes for travels, Safdi says: “They would usually start talking about that they have love for Islam, they want to live in an Islamic state, they want to live somewhere where shariah is implemented. When you go deeper with them in the conversation, when conversations are more meaningful, I would hardly hear them speak about Islamic state or the implementation of shariah. All I would hear are the injustices they have experienced in the past: racism, discrimination, poverty, lack of opportunity. […] The majority of them are very young people. Many of them haven’t even reached the age of 18. They are frustrated, alienated socially. Young people who are in search of identity, a meaning in life. Young people that did not feel at home in their own countries where they were born, who felt they were not appreciated” (Safdi, 2020)

Examples testifying to the same fact can be multiplied. In his piece where he presents the case of two ISIL terrorists, Mehdi Hassan says before their journey to Syria, the two books they bought from Amazon were “Islam for Dummies” and “Koran for Dummies.” He further continues:

In 2008, a classified briefing note on radicalization, prepared by MI5’s behavioural science unit, was leaked to the Guardian. It revealed that, “far from being religious zealots, a large number of those involved in terrorism do not practice their faith regularly. Many lack religious literacy and could . . . be regarded as religious novices.” The analysts concluded that “a well-established religious identity actually protects against violent radicalization”, the newspaper said. (Hassan, 2014)

A recent study conducted by German security authorities by analyzing data on 910 individuals who traveled to the Levant actually supports the argument that “a well-established religious identity actually protects against violent radicalization”. The study revealed that 17% of the total number were converts. What is more, converts comprised at least one third of female departees (Heinke, 2017).

Safdi’s testimony also hints at the interaction between radicalization and polarization. In line with this, in their article on challenges to create counter-narratives, Prof. Speckhard and Dr. Shajkovci say:

The main recruiting pool for groups like ISIS are Muslim converts and second-generation Muslim immigrant communities who have not found the promises of the EU to match their daily realities. In formal and informal interviews with hundreds of EU citizens to date, ICSVE researchers have found sentiments of Islamophobia, discrimination, and marginalization to be widely prevalent in their daily lives and experiences. (Speckhard, 2018)

So where is religion in this equation? “Religion” comes actually into play mainly in two areas. The first one is the fact that religion is in most cases an inalienable part of an individual’s identity. The rise of far-right, xenophobia and identity-based discriminatory approaches among politicians and society has been a factor to deepen the divide among different religion groups and polarize them.

Second and more importantly, religion plays an important role in the justification of the violence. It should be acknowledged that worldviews are open to different interpretations (hermeneutics) and the violent interpretation is not unavoidable. These violent interpretations do not constitute the essence and original reading of respective religions but form perversions of it. Those perversions create foundations of ideologies that feed and fuel violent groups. According to Walter, irrespective of whether they believe in underlying core tenets or not, embracing extremist ideologies help leaders of such groups overcome collective action problem, using the ideology as vehicle or tool to raise units of men ready to accept the cost of fighting and death (Walter, 2017).

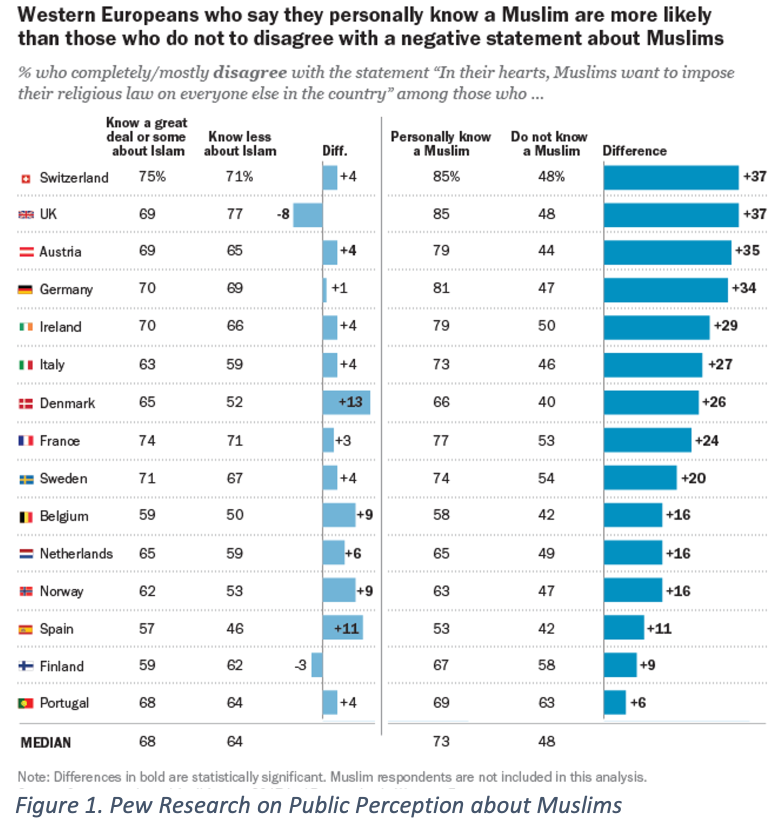

3. One Important Survey to Become Source of Inspiration for EDUC8

Pew research conducted between April – August 2017 influenced conceptualization of EDUC8. The non-Muslim respondents in 15 European countries were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the statement that “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else in the country.” The survey results show, there is less of a difference between those who say they know “a great deal” or “some” about Islam and those who know “not very much” or “nothing at all.” On the contrary, a sizable difference is observed among respondents that personally know a Muslim and those do not. In statistical terms, the mean of difference for 15 countries is 21,31 percent. It is of note that in two countries, Switzerland and UK, more than eight-in-ten (85%) of those who say they know a Muslim disagree with the statement, compared with just 48% of those who do not know a Muslim. This brings us to the conclusion that getting to know each other among individuals from different faiths helps to overcome prejudices or stereotypes (Gardner & Evans, 2018)

4. REDCo and Its Findings

REDCo is the first substantial research project on religion and education financed by the European Commission, which ran from March 1, 2006 until March 31, 2009. Qualitative and quantitative research was conducted in eight countries (Germany, England, France, The Netherlands, Norway, Estonia, Russia, Spain) mainly focusing on religion in the lives and schooling of students in the 14–16 age group. The study dealt with different perspectives of the general question on how far religion is a factor of stereotypes and conflicts or a source of dialogue and peaceful living together. Here are some key findings of the study:

- Those who learn about religious diversity in school are more willing to enter into conversations about religions and world views with students from other backgrounds than those who do not have this opportunity for learning.

- Students believe that the main preconditions for peaceful coexistence between people of different religions are knowledge about each other’s religions and worldviews, shared interests, and joint activities.

- Students for whom religion is important in their lives are more likely to respect the religious background of others and value the role of religion in the world.

- Most students would like to see school dedicated more to teaching about different religions than to guiding them towards a particular religious belief or worldview (REDCo Consortium, 2009).

5. EDUC8 Connects the Dots to Propose “Original” Methodology, Content and Tools

Based on the abovementioned facts and insight, EDUC8 Project was conceptualized with the aims to answer especially the following EU needs:

- Radicalization and polarization are two faces of the same coin that feed and catalyze each other. There is need for developing a comprehensive effort to build resilience against radicalization towards all types of violence while building tolerance towards the “other” and differences.

- Religions and worldviews are open to different interpretations (hermeneutics). While the violent interpretation is not unavoidable, it does not constitute the essence of the respective worldview system and is even a perversion of it. A well-established religious identity protects against violent radicalization. It is crucial to build resilience by convincing the young people that there is no religious legitimacy in killing innocent people let alone being incumbent upon them.

- In any authentic religion and worldview, there is a potential to change, to criticize, to overrule, to transform violence into tolerance and peace. There is urgent need to recognize this potential in the other and feel invited and challenged to discover this potential.

- There is need for preventive work that will target the young as early as secondary school level, teach them representation of different religions, to help them develop respect and mutual understanding, and teach them how to understand religion and religious texts to enable them to withstand extremist ideologies. Diversity and friendships among diverse groups is the remedy of intolerance and violence.

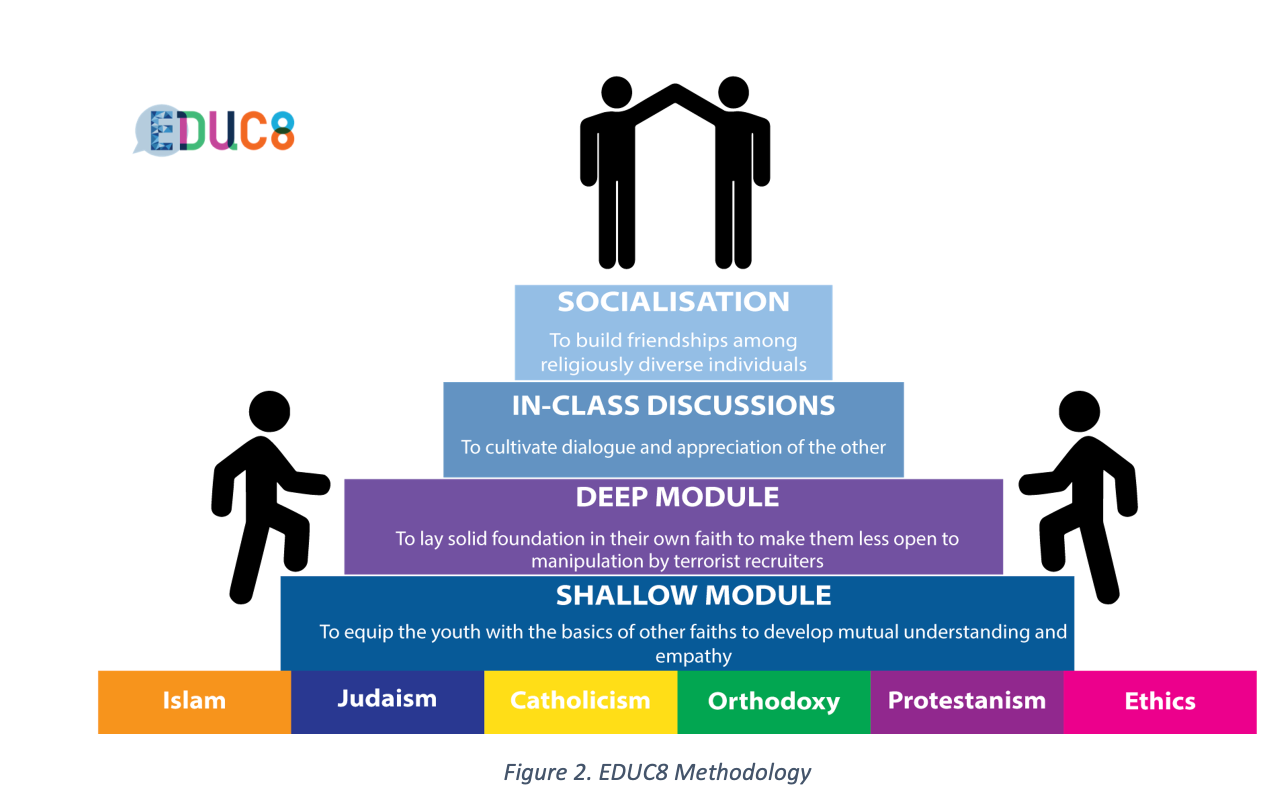

To attain those goals, EDUC8 proposes a four-step methodology that involves equipping the audience with knowledge of the other (shallow module), a good understanding of the own worldview (deep module), reaching mutual understanding and appreciation through dialogue (in-class discussion) and building friendships through smart encounters (socialization). The key component of this methodology is in-class discussion which develops required skills in 5 steps. Those are:

- Knowledge of the tradition on the topic + critical issues (from the exterior): Presenting the basic facts and figures of a certain ethical or religious tradition on a topic, including also misunderstandings, prejudices and pitfalls for people who are not involved in this tradition.

- Understanding the tradition from within: Explaining the inner dynamic of an ethical or religious tradition on a topic, trying to understand from within.

- Respect, acknowledgment, appreciation of the other: Opening oneself to the witness of the other, to the strength and beauty of his/her tradition, to the philosophical, moral, esthetic or spiritual splendor of the other living his or her tradition. Giving and accepting hospitality in the tradition of the other

- Learning from the other through dialogue: Entering into dialogue with the other, trying to understand, asking questions, formulating critiques, looking for communalities and differences, etc.

- Being transformed oneself through the encounter with the other: Returning to one’s own tradition or beliefs, see how the encounter with the other has changed (challenged, enriched, deepened, etc.) my understanding of the other and of myself.

Alongside its methodology, EDUC8 also introduces “new-school” elements for the target groups. Its main outputs, the religious education program, is embedded onto web- and tablet platforms in three languages: English, French and Dutch.[7] The whole program is structured around storytelling (scenario-based), interactive, and harnesses popularity of tablets and their ability to address three senses (sight, hearing, touch).

So far, EDUC8 has built up a religious educational program that extends over six religions / philosophies / world systems (Judaism, Catholicism, Islam, Orthodoxy, Protestantism and Non-Confessional Ethics) in 26 modules on four main subjects:

- Encounter with the other: dealing with diversity

- Encounter with sacred texts: texts of violence

- Encounter with the environment: social and ecological issues

- When encounter becomes conflict: just war and just peace

The project was implemented in PHTI, a public secondary school in Ghent, Belgium for 8 weeks between 22 March – 28 May, covering it in entirety. The project received extremely positive feedback from both teachers and students. The principal of the school commented on the project saying:

We believe very strongly in the strength of this way of working together across ideological boundaries. You have launched a wonderful project that certainly deserves to be further rolled out and refined. We also want to thank you warmly for the warm cooperation and we hope that in the near future we will be able to walk the same road together.

In my opinion, this form of coteaching and participation of students and teachers in a critical and at the same time very respectful dialogue is a nice alternative to the LEF story which, in my opinion, does not contain the same powerful ‘coat hooks’ as your story!

Philip Quarles van Ufford, the Protestantism teacher in the school of implementation shares his thoughts as follows:

The strength of the project, in my opinion, lays in the right combination of a well-prepared presentation of the 6 recognized philosophies of life on the one hand and – building on that – the critical reflection on the difficult themes on the other hand. This critical reflection was first done within the own circle, after which a meeting and discussion took place about these themes together with students of other confessions. This set-up had a unifying effect, clarified questions and created understanding.

Currently the project is in implementation in one prison (Antwerp, Belgium), one juvenile penitentiary (Kempen, Belgium), one NGO in Finland (implementation in youth work), four schools in Slovenia and four schools in Greece. It is of note that there is no formal religious education in Slovenia and EDUC8 will be the first to make an exception with the ongoing implementation.

6. Policy Recommendations

EDUC8 Project with the excellence of its methodology, strong pedagogical foundations, an engaging narrative style and an attractive visual design is candidate to offer a sound approach to build resilience among secondary school students across Europe against radicalization and polarization. To better exploit the project results, we recommend:

- Development of innovative approaches to learning about different religions and worldviews in their complexity and inner diversity. EDUC8 shallow modules can be used for this purpose in MS lower secondary schools as part of religious educational curriculum. In the shallow modules, EDUC8 offers a learning from within (a presentation of the religion by a member of that religion, with a positive attitude towards it).

- Development of innovative approaches to tackle generally avoided hard questions in religions and real dangers. EDUC8 deep modules, especially if used after completion of shallow modules can create a starting point. EDUC8 does not avoid a presentation of the dangerous potential of a religion around a certain topic and often this challenge is brought in the form of a ‘Fremd prophecy’: someone from an external perspective challenges pre-supposition. There is a two steps method:

- A first naivety violent interpretation

- A second naivety peaceful re-interpretation

- Development of an intra-class interfaith approach founded upon mutual respect and tolerance. The main element of EDUC8 methodology, in-class discussion, can be operationalized and become a norm within schools. The “Teacher’s Training Guide” showcases one form of co-teaching and participation of students and teachers in a critical and at the same time very respectful dialogue.

- The project can be further funded by the EC or MS to add more subjects to the existing four modules to increase its impact.

- The project can be further funded by more MS or third countries to adapt its products extended to the funder’s native and/or additional languages.

Bibliography

Belga. (2021, March 08). Drie minderjarigen geven zichzelf aan na moord op homoseksuele man in Bevers park. Retrieved March, 2021 from De Standaard: https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20210307_97745790

Gardner, S., & Evans, J. (2018, July 24). In Western Europe, familiarity with Muslims is linked to positive views of Muslims and Islam. From Pew Research Center: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/24/in-western-europe-familiarity-with-muslims-is-linked-to-positive-views-of-muslims-and-islam/

Hafez, M. (2015). The radicalization puzzle: a theoretical synthesis of empirical approaches to homegrown extremism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 38, 958-975.

Hassan, M. (2014, August 21). What the Jihadists Who Bought ‘Islam For Dummies’ on Amazon Tell Us About Radicalisation. From The Huffington Post: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/mehdi-hasan/jihadist-radicalisation-islam-for-dummies_b_5697160.html

Heinke, D. H. (2017). German Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq: The Updated Data and its Implications. CTC Sentinel, 10(3), 17-22.

Olsson, P. A. (2014). The Making of a Homegrown Terrorist. Praeger.

Pew Research Center. (2016, July 11). Views of Muslims more negative in eastern and southern Europe. Retrieved February, 2019 from Pew Research Center: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2016/07/11/europeans-fear-wave-of-refugees-will-mean-more-terrorism-fewer-jobs/ga_2016-07-11_national_identity-00-01/

Povoledo, E., & Graham, R. (2021, March 15). Vatican Says Priests Can’t Bless Same-Sex Unions. Retrieved October, 2021 from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/world/europe/vatican-same-sex-unions.html

REDCo Consortium. (2009). Religion in Education. A contribution to Dialogue or a factor of Conflict in transforming societies of European countries? Final Activity Report.

Safdi, R. (2020, June 10). Can an ISIS Terrorist be Rehabilitated and Reintegrated into Society? Retrieved August, 2020 from ICSVE: https://www.icsve.org/can-an-isis-terrorist-be-rehabilitated-and-reintegrated-into-society/

Speckhard, A. (2018, November 27). PERSPECTIVE: Challenges in Creating, Deploying Counter-Narratives to Deter Would-be Terrorists. Retrieved 2019, October from Homeland Security Today.US: https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/terrorism-study/perspective-challenges-in-creating-deploying-counter-narratives-to-deter-would-be-terrorists/

Speckhard, A., Shajkovci, A., & Yayla, A. (2018). Defected from ISIS or Simply Returned, and for How Long?– Challenges for the West in Dealing with Returning Foreign Fighters. Homeland Security Affairs, 14, 1-21.

Sultan, O. (2020). Between Rock and a Hard Place-French Vision of Radicalisation and an Alternative Perspective. Horizon Insights, 3(4), 13-20.

Walter, B. F. (2017). The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars. International Security, 42(2), 7-39.

[1] EDUC8 – EDUCATE TO BUILD RESILIENCE Project has received funding from the European Union’s Internal Security Fund — Police under grant agreement No: 871090. This work was supported by the same funding instrument.

[2] Radicalization is defined as:“a process during which a person or a group of persons experiences such influences that this person or this group of persons will at some point, be mentally moulded or disposed to commit terrorist acts” (act of 30 November 1998 governing the intelligence and security services – Art 3,15°; non official translation). retrieved from Plan R The Action Plan Against Radicalism, Federal Public Services Home Affairs, https://www.besafe.be/sites/default/files/2019-06/planr_en.pdf.

[3] Polarization can be defined as “the strengthening of opposition between [persons or] groups in society that results or can result in (the exacerbation of) tensions between these [persons or] groups and create risks for the security of society” Source: Plan global de Sécurité et de Prévention de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale, Brussels Observatory for Prevention and Security (BPS / BPV)), https://bps-bpv.brussels/sites/default/files/2019-05/POLARISATION_ET_RADICALISATION.pdf.

[4] Onur Sultan is Research Fellow at Beyond the Horizon and the Coordinator of the EDUC8 Project.

[5] Didier Pollefeyt is full professor at the Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies of KU Leuven, Belgium. He holds the Chair of the Center for Teacher’s Training in Religion and the Center for Peace Ethics of KU Leuven.

[6] Here, we include non-confessional ethics among other religions thought at school. To maintain integrity and for the sake of conciseness we did not revert to openly state this. Here and in the following lines, religion within context of school contains this critical and equally important world system or life philosophy.

[7] At the time of writing this policy brief, the work to build the application is underway. But the final version will be found on android and apple stores.

Contact Us

+32 (0) 2 801 13 57-58

Davincilaan 1, 1932 Brussels Belgium

© 2020-2025 All Rights Reserved